The Philosophy of Data Privacy: Why We're Building Programs That Miss the Point

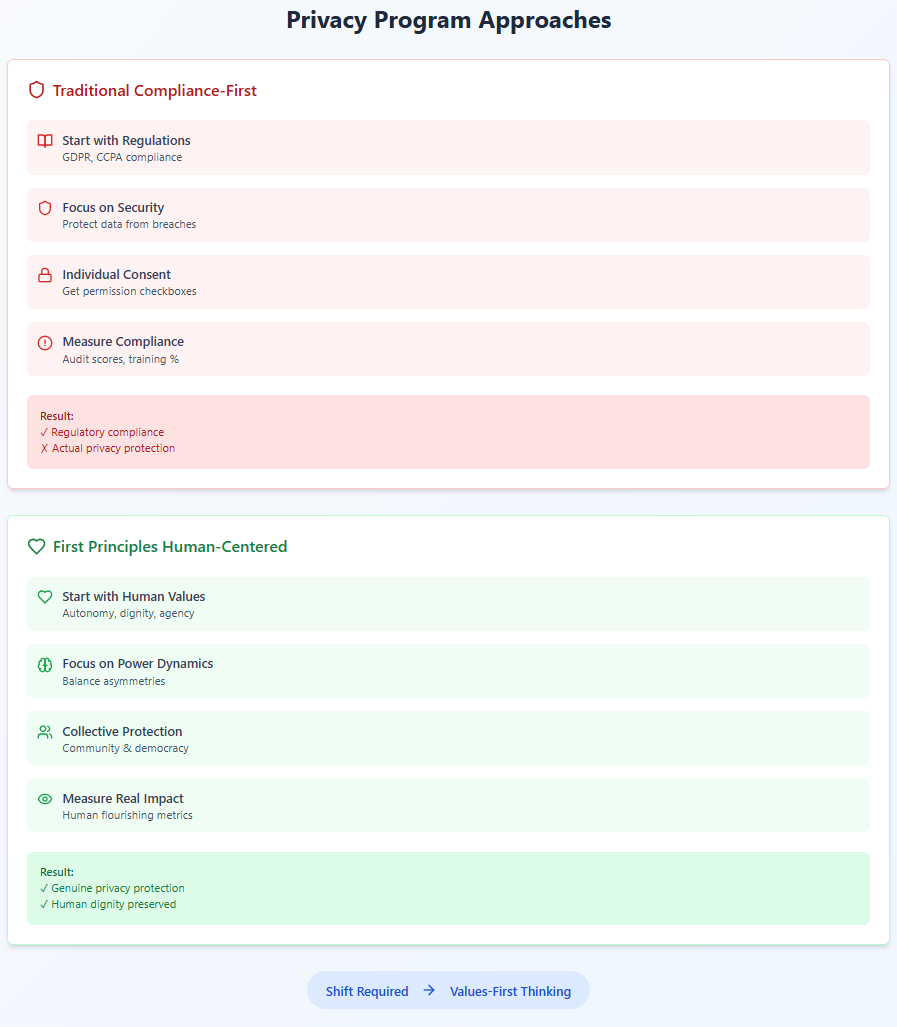

The Bottom Line Up Front: Data privacy isn't fundamentally about compliance or technology—it's about power asymmetries and human autonomy in the digital age. Understanding this philosophical foundation is essential for building privacy programs that actually protect people rather than just checking boxes. Most organizations approach privacy backwards, starting with regulations rather than principles, which is why so many privacy programs feel disconnected from their stated purpose of protecting individuals.

The Privacy Paradox: Why Our Programs Feel Empty

Here's a scene that plays out in conference rooms across the corporate world: A Chief Privacy Officer stands before the board, proudly displaying metrics about GDPR compliance rates, privacy training completion percentages, and the number of data processing agreements signed. The board nods approvingly. The CPO gets their budget approved. Everyone feels good about "taking privacy seriously."

Meanwhile, that same company's customers have no meaningful understanding of how their data is being used, no real control over its collection, and no practical ability to opt out without losing access to essential services. The privacy program is a success by every metric that matters to regulators and auditors. It's a failure by the only metric that should matter: whether it actually protects people's autonomy and dignity in their digital lives.

This disconnect isn't accidental. It reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what privacy is and what it's meant to accomplish. As Helen Nissenbaum writes in Privacy in Context, "Privacy is not a right to secrecy or a right to control, but a right to appropriate flow of information." Yet most privacy programs treat it as a compliance exercise—a set of boxes to check rather than a fundamental value to protect.

The philosopher Luciano Floridi puts it even more starkly in The Fourth Revolution: "Privacy is not about hiding things. It's about being able to control who knows what about you and under what circumstances." But when was the last time a corporate privacy program genuinely increased users' control over their information? When did a privacy policy actually clarify rather than obscure?

What Is Data Privacy Actually Trying to Accomplish?

To understand what privacy programs should be doing, we need to start with first principles. What is privacy for? Why does it matter? And how did we end up with programs that seem so disconnected from these fundamental purposes?

The Philosophical Foundations: Autonomy, Dignity, and Power

At its core, privacy is about preserving human autonomy in contexts where information asymmetries create power imbalances. This isn't a new idea. In their groundbreaking 1890 Harvard Law Review article "The Right to Privacy," Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis weren't primarily concerned with keeping secrets. They were worried about how new technologies (in their case, portable cameras and mass-circulation newspapers) were changing the balance of power between individuals and institutions.

They wrote: "Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person, and for securing to the individual... the right 'to be let alone.'" But this "right to be let alone" wasn't about isolation—it was about maintaining zones of autonomy where individuals could develop their thoughts, relationships, and identities without constant observation and judgment.

The philosopher Jeremy Bentham's concept of the Panopticon illustrates why this matters. In a prison where inmates might be watched at any time but can never know when they're being observed, behavior changes fundamentally. As Michel Foucault observed in Discipline and Punish, "Visibility is a trap... He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power."

This is the deep fear that animates genuine privacy concerns: not that someone will learn our secrets, but that constant observation will shape who we become. As Shoshana Zuboff argues in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, "The real psychological truth is that sudden major changes in our privacy status are anxiety-provoking... But the deeper truth is that these abrupt transitions are merely the visible eruptions of a more profound transformation."

The Modern Context: Digital Panopticons and Behavioral Futures

Today's privacy challenges would astonish Warren and Brandeis. It's not just that we're observed—it's that our observations are processed, analyzed, and used to predict and influence our future behavior. Zuboff calls this "surveillance capitalism," where "human experience is free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales."

Consider a simple example: You search for information about depression. That search is recorded, analyzed, combined with thousands of other data points about you, and used to build a model of your mental state. That model might determine what ads you see, what prices you're offered, whether you're approved for insurance, or if you're selected for a job interview. The issue isn't that someone knows you searched for depression information—it's that this knowledge is used to exercise power over your future possibilities.

As Cathy O'Neil documents in Weapons of Math Destruction, these algorithmic systems often "damage the lives of individuals and amplify inequality." But most privacy programs don't even attempt to address these systemic issues. They focus on narrow compliance questions: Did we get consent? Did we post a privacy notice? Did we respond to the data subject request within 30 days?

What Privacy Is Trying to Protect

Drawing from privacy scholarship and philosophy, we can identify four fundamental values that privacy seeks to protect:

1. Informational Self-Determination

The German Constitutional Court coined this term in 1983, defining it as "the authority of the individual to decide himself, on the basis of the idea of self-determination, when and within what limits information about his private life should be communicated to others."

This isn't just about control—it's about maintaining the conditions necessary for authentic self-development. As the court noted, "A person who cannot with sufficient certainty assess which information about himself is known in certain areas of his social environment, and who cannot sufficiently assess the knowledge of potential communication partners, can be substantially restricted in his freedom to plan and decide."

2. Contextual Integrity

Helen Nissenbaum's theory of "contextual integrity" argues that privacy violations occur when information flows inappropriately between contexts. Information shared with a doctor has different norms than information shared with a friend or employer. Privacy programs should protect these contextual boundaries.

As Nissenbaum writes, "What people care most about is not simply restricting the flow of information but ensuring that information flows appropriately." A privacy program focused on contextual integrity would ask not just "Did we get consent?" but "Is this use of data consistent with the context in which it was shared?"

3. Relational Autonomy

Privacy isn't just individual—it's relational. We need privacy to develop intimate relationships, to engage in political organizing, to explore new ideas without immediate judgment. As Julie Cohen argues in Configuring the Networked Self, "Privacy shelters dynamic, emergent subjectivity from the efforts of commercial and governmental actors to render individuals and communities fixed, transparent, and predictable."

This relational dimension is often completely absent from corporate privacy programs, which treat privacy as a matter of individual choice rather than collective protection.

4. Democratic Participation

Privacy is essential for democratic society. Without spaces free from surveillance, there can be no genuine political dissent, no challenging of power structures, no development of alternative visions for society. As Neil Richards argues in Intellectual Privacy, "New ideas often develop best away from the intense scrutiny of public exposure; intense scrutiny of the intellectual process can chill experimentation and dissent."

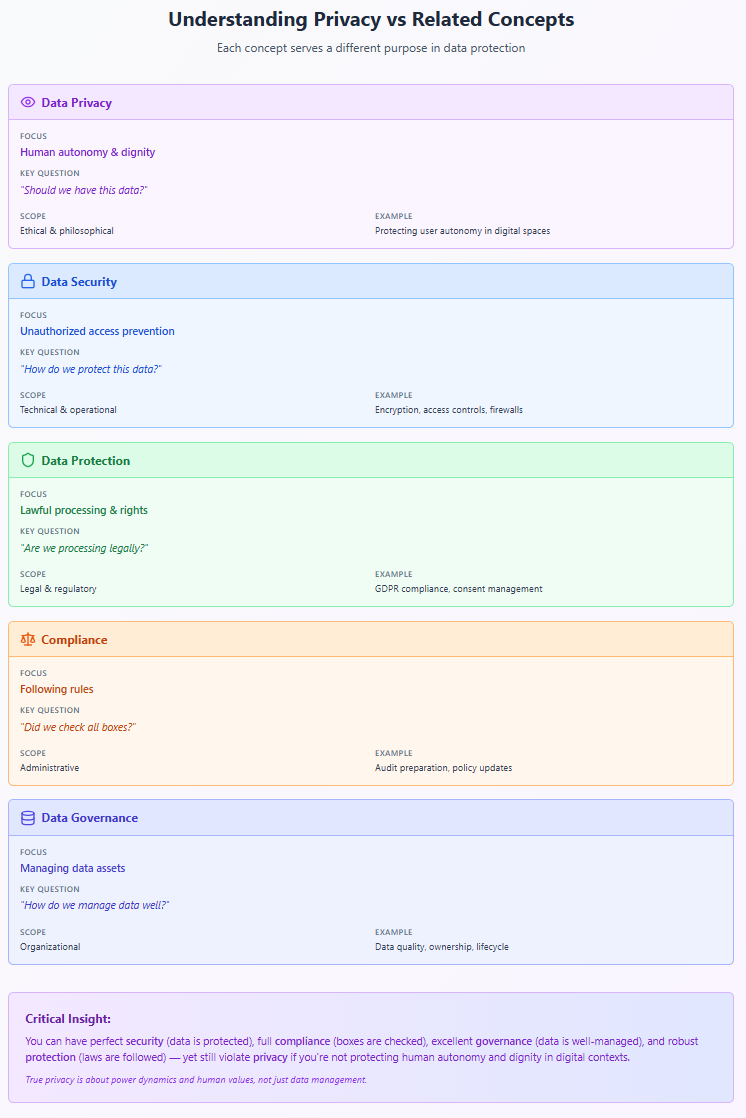

The Taxonomy Problem: How Privacy Differs from Security, Protection, and Compliance

One reason privacy programs fail is that organizations conflate privacy with related but distinct concepts. Understanding these differences is crucial for building programs that actually protect privacy rather than just managing data.

Data Privacy vs. Data Security

Data security is about protecting data from unauthorized access, use, or destruction. It's a necessary condition for privacy but not sufficient. You can have perfect security—unbreakable encryption, impenetrable firewalls, flawless access controls—and still have terrible privacy if you're using that perfectly secured data in ways that violate people's autonomy and dignity.

As Bruce Schneier writes in Data and Goliath, "Security is about protecting data from unauthorized access. Privacy is about protecting people from the powerful." A security-focused approach asks, "How do we keep this data safe?" A privacy-focused approach asks, "Should we have this data at all?"

Data Privacy vs. Data Protection

Data protection, particularly in the European context, is broader than security but still narrower than privacy in its philosophical sense. Data protection regulations like GDPR focus on lawful processing, purpose limitation, and data subject rights. These are important, but they still operate within a framework that accepts large-scale data collection as legitimate.

True privacy protection would question the entire apparatus of surveillance capitalism, not just regulate its operations. As Evgeny Morozov argues in To Save Everything, Click Here, "The problem with digital surveillance is not just that it's creepy or that it violates our privacy. It's that it gives the powerful new ways to control and manipulate us."

Data Privacy vs. Compliance

Compliance is about following rules. Privacy is about protecting values. You can be fully compliant with every privacy regulation on earth and still operate systems that surveil, manipulate, and control people in ways that violate their fundamental autonomy.

Consider the cookie consent banners that plague the modern web. They're a compliance solution to a privacy problem, but they don't actually protect privacy. As Woodrow Hartzog notes in Privacy's Blueprint, "Notice and choice regimes are a failed model for privacy protection... They place the burden on individuals to protect themselves against powerful and sophisticated data collectors."

Data Privacy vs. Data Governance

Data governance is about managing data assets effectively—ensuring quality, establishing ownership, defining appropriate use. It's organizational and operational. Privacy is ethical and political. Good governance can support privacy, but it can also enable more sophisticated surveillance.

The question for privacy isn't "Are we managing our data assets well?" but "Are we respecting the humanity and autonomy of the people behind the data?"

Why Most Organizations Approach Privacy Backwards

Understanding why organizations get privacy wrong requires examining the incentive structures and mental models that shape corporate privacy programs. The backwards approach isn't usually malicious—it's a predictable result of how privacy responsibilities are typically assigned and measured.

Starting with Regulations Rather Than Principles

Most privacy programs begin with a compliance mandate: "We need to comply with GDPR/CCPA/PIPEDA/etc." This immediately frames privacy as a legal problem rather than an ethical one. The organization asks, "What do we have to do?" rather than "What should we do?"

This regulatory-first approach creates several problems:

Checkbox Mentality: Privacy becomes a list of requirements to satisfy rather than a value to uphold. Organizations do the minimum necessary to avoid penalties rather than genuinely protecting privacy.

Reactive Posture: Programs respond to new regulations rather than proactively identifying and addressing privacy risks. They're always playing catch-up with the latest requirements.

Narrow Scope: Regulatory compliance focuses on specific types of data (personal information) and specific activities (processing), missing broader privacy implications of organizational practices.

Adversarial Dynamics: Privacy becomes something imposed on the organization from outside rather than a value embraced from within. This creates resistance and workarounds rather than genuine commitment.

The Expertise Problem: Lawyers, Engineers, and Ethicists

Privacy sits at the intersection of law, technology, and ethics, but most privacy programs are dominated by one perspective. When lawyers lead, privacy becomes compliance. When engineers lead, privacy becomes security. When ethicists lead (rare in corporate settings), privacy becomes philosophy disconnected from operational reality.

As danah boyd observes in It's Complicated, "Privacy is not a static construct. It is an ongoing process of negotiating boundaries." This negotiation requires multiple perspectives, but most organizations lack the interdisciplinary leadership necessary for genuine privacy protection.

Measuring the Wrong Things

Peter Drucker's maxim "What gets measured gets managed" applies perversely to privacy programs. Organizations measure what's easy to quantify:

- Number of privacy policies updated

- Percentage of employees trained

- Data subject requests processed

- Time to breach notification

- Compliance audit scores

But these metrics don't capture whether privacy is actually being protected. They don't measure:

- Whether people understand how their data is used

- Whether they have meaningful choices about data collection

- Whether data use respects contextual norms

- Whether people feel surveilled or manipulated

- Whether the organization's data practices support or undermine human autonomy

The Business Model Problem

Perhaps the deepest reason organizations approach privacy backwards is that genuine privacy protection often conflicts with business models built on data extraction. As Shoshana Zuboff documents extensively, many modern businesses depend on what she calls "behavioral surplus"—data about people that can be used to predict and influence their behavior.

In this context, privacy programs become exercises in privacy theater—creating the appearance of protection while enabling continued extraction. The program's real purpose isn't protecting privacy but legitimizing its violation.

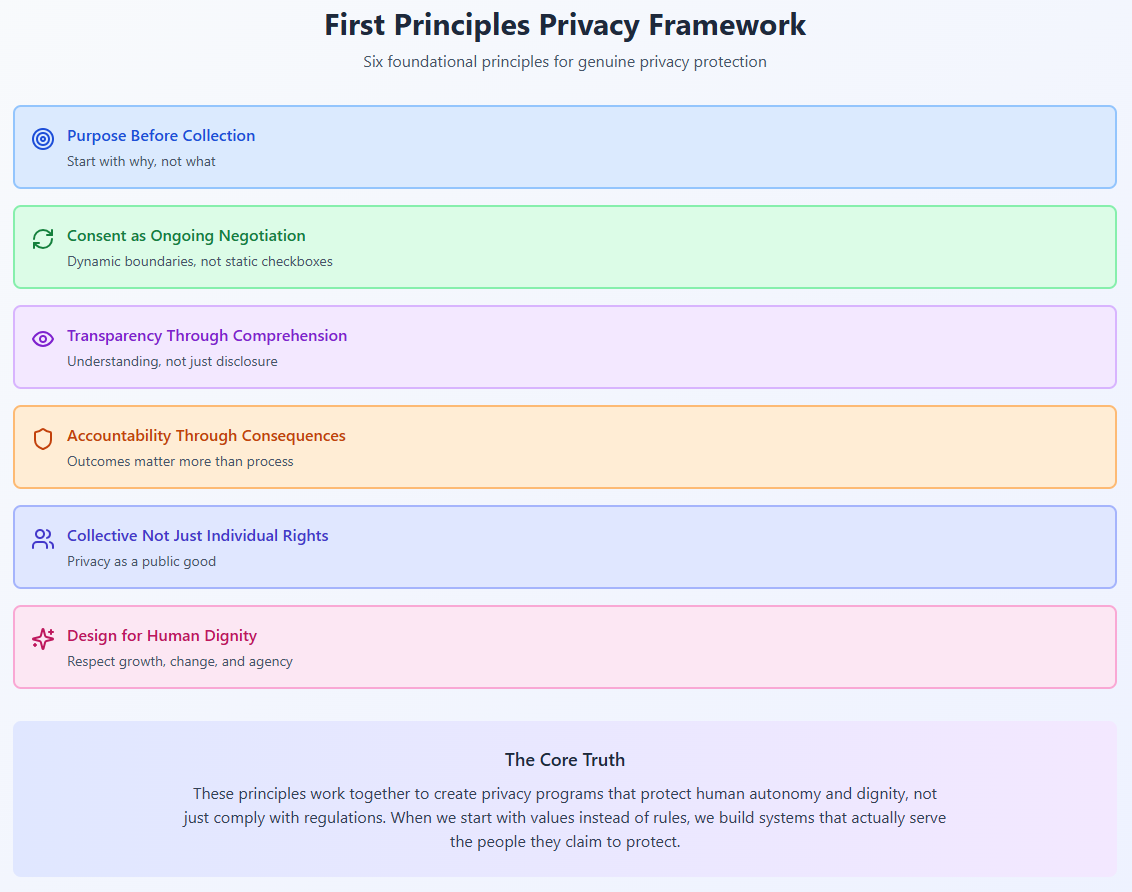

What Would Data Privacy Look Like from First Principles?

If we were designing privacy programs from scratch, starting with the philosophical foundations rather than regulatory requirements, what would they look like? This thought experiment helps us see how far current approaches have strayed from privacy's core purposes.

Principle 1: Purpose Before Collection

A first-principles privacy approach would start with purpose, not data. Before collecting any information, organizations would need to articulate:

- Why is this data necessary?

- What specific purpose will it serve?

- How does this purpose benefit the data subject?

- What's the minimum data needed for this purpose?

- When will this purpose be fulfilled and the data deleted?

This reverses the current dynamic where organizations collect first and find purposes later. As Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Kenneth Cukier warn in Big Data, "In the big-data age, the value of information no longer resides solely in its primary purpose... Data's value shifts from its primary use to its potential future uses."

Principle 2: Consent as Ongoing Negotiation

Current consent models treat privacy as a binary choice made at a single moment. A first-principles approach would recognize consent as an ongoing negotiation that can be revised as contexts change.

This might involve:

- Regular check-ins about data use

- Easy mechanisms to adjust privacy preferences

- Clear communication when purposes change

- Default expiration of consent after reasonable periods

- Granular controls over different uses

As Nancy Baym argues in Personal Connections in the Digital Age, "Privacy is not about setting rules and forgetting them. It's about ongoing boundary management in changing contexts."

Principle 3: Transparency Through Comprehension

Current transparency efforts focus on disclosure—lengthy privacy policies that technically inform but practically obscure. First-principles transparency would focus on comprehension:

- Plain language explanations of data practices

- Visual representations of data flows

- Concrete examples of how data is used

- Regular reports on actual data use

- Open channels for questions and clarifications

The goal isn't legal protection through disclosure but genuine understanding that enables informed choice.

Principle 4: Accountability Through Consequences

Current accountability mechanisms focus on process—did you follow the rules? First-principles accountability would focus on outcomes—did you protect privacy? This might involve:

- Regular assessment of privacy impacts on real people

- Meaningful penalties for privacy violations

- Compensation for privacy harms

- Public reporting of privacy protection effectiveness

- Independent oversight with real power

Principle 5: Collective Not Just Individual Rights

Current privacy frameworks focus on individual rights—access, correction, deletion. A first-principles approach would recognize privacy's collective dimensions:

- Community consent for data practices affecting groups

- Protections against discriminatory data use

- Limits on data practices that undermine democracy

- Support for privacy-preserving collective action

- Recognition of privacy as a public good

Principle 6: Design for Human Dignity

Ultimately, a first-principles privacy approach would measure success not by compliance rates but by whether it upholds human dignity in digital contexts. This means:

- Respecting people's capacity for growth and change

- Protecting spaces for experimentation and mistake-making

- Supporting authentic self-presentation

- Preventing manipulation and coercion

- Enabling genuine choice and agency

The Path Forward: Building Privacy Programs That Matter

Moving from current privacy theater to genuine privacy protection requires fundamental shifts in how we think about and implement privacy programs. This isn't just about adding new requirements or improving existing processes—it's about reimagining privacy's role in organizational life.

Starting with Values, Not Compliance

Organizations serious about privacy need to begin with values clarification. What do we believe about human autonomy? How do we balance organizational needs with individual dignity? What kind of relationship do we want with the people whose data we handle?

These aren't just philosophical questions—they're practical foundations for program design. An organization that values human autonomy will make different choices than one focused solely on legal compliance.

Building Interdisciplinary Leadership

Privacy is too complex for any single discipline to handle alone. Effective privacy programs need leadership that combines:

- Legal expertise to navigate regulatory requirements

- Technical knowledge to understand possibilities and constraints

- Ethical grounding to maintain focus on human values

- Business acumen to find sustainable solutions

- Communication skills to engage diverse stakeholders

This might mean creating new organizational structures—privacy boards that include ethicists and user advocates alongside lawyers and engineers, or rotating leadership models that bring different perspectives to the forefront at different times.

Developing New Metrics

If current metrics miss the point, what should we measure instead? First-principles privacy metrics might include:

- User comprehension of data practices (tested through actual understanding, not just exposure to information)

- Meaningful choice availability (measured by viable alternatives, not just yes/no options)

- Contextual integrity maintenance (assessed through user perception of appropriate use)

- Power balance indicators (evaluating whether data practices increase or decrease user agency)

- Dignity preservation measures (tracking whether people feel respected and autonomous)

These metrics are harder to quantify than compliance rates, but they better capture whether privacy is actually being protected.

Creating Feedback Loops

Privacy protection requires ongoing adjustment based on how practices affect real people. This means creating mechanisms for:

- Regular user research on privacy impacts

- Channels for privacy concerns and suggestions

- Rapid response to identified problems

- Public reporting on privacy protection efforts

- External assessment of program effectiveness

The goal is creating what organizational theorists call a "learning system"—one that continuously improves based on feedback rather than remaining static once implemented.

Embracing Privacy as Competitive Advantage

Perhaps most importantly, organizations need to stop seeing privacy as a burden and start seeing it as an opportunity. In a world of increasing surveillance and manipulation, genuine privacy protection can be a powerful differentiator.

This doesn't mean privacy theater—it means building business models that don't depend on surveillance, creating products that empower rather than exploit, and fostering relationships based on respect rather than extraction.

The Deeper Truth About Privacy

As we've explored, data privacy isn't fundamentally about hiding information or complying with regulations. It's about preserving the conditions necessary for human flourishing in a digital age. It's about maintaining spaces for growth, experimentation, and authentic self-development. It's about protecting the relational foundations of intimate life and democratic society.

Current privacy programs fail because they miss this deeper purpose. They focus on data protection mechanics while ignoring privacy's philosophical foundations. They measure compliance rates while privacy itself erodes. They create elaborate processes that obscure rather than illuminate how data is actually used.

Building privacy programs that matter requires returning to first principles. It means asking not "What must we do?" but "What should we do?" It means measuring success not by audit scores but by whether people maintain autonomy and dignity in their digital lives. It means recognizing privacy not as an individual preference but as a collective necessity for human flourishing.

The path forward isn't easy. It requires challenging business models built on surveillance, developing new organizational capabilities, and creating metrics that capture what really matters. But the alternative—continued erosion of privacy behind a facade of protection—threatens the foundations of human autonomy and democratic society.

As we build the next generation of privacy programs, we have a choice. We can continue the theater of compliance, checking boxes while privacy itself disappears. Or we can return to privacy's philosophical roots and build programs that genuinely protect human autonomy in the digital age. The technical challenges are significant, but they pale compared to the ethical imperative.

Privacy matters not because we have something to hide, but because we have something to protect: our capacity to be human in a digital world. Programs that understand this truth have a chance of actually protecting privacy. Those that don't will continue to fail, no matter how many boxes they check.

This is the first in a series exploring data privacy from philosophical and practical perspectives. Next, we'll examine how to assess privacy needs in your organization without being a legal expert, and build frameworks for privacy that honor both regulatory requirements and human values.